Medication Safety

Introduction

Ensuring medication safety has always been a key focus of pharmacy profession. Some of the findings in the Institute of Medicine's (IOM) report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, include

- Medical errors are common.

- Medical errors are tragic.

- Medical errors are expensive.

- Medical errors are preventable.

Medication Error

The term "medication error" is used to describe any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient or consumer.

- Such events may be related to professional practice and healthcare products, procedures and systems, including prescribing; order communication; product labelling, packaging and nomenclature; compounding; dispensing; distribution; administration; education; monitoring; and use.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) has developed a standard system for categorizing medication errors by 12 types.

National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention Error Category Index classifies an error according to the severity of the outcome.

NOTE: Potential errors (near misses, good catches) are errors caught prior to administering medication to the patient.

Causes of Medication Errors

The causes of medication errors are varied and complex. They usually involve multiple causes and are the result of weakness in the medication-use system, in addition to human behavioural choices.

When an accident happens in an organization, two different approaches are possible to explain its origin and dynamics.

- Individual blame logic aims at finding the guilty individuals.

- Organizational function logic aims to identify the organization factors that favoured the occurrence of the event.

To create lasting improvement and significantly reduce the potential for future errors, the focus must be on what caused the error, not who caused the error.

- It is unrealistic to expect human performance to be free of errors because all humans make mistakes.

- Also, as depicted in "Swiss Cheese" model, an accident happen as a consequence of multiple failures in the system.

A root cause analysis (RCA) enables us to identify the most probable causative factors of medication errors, allowing us to take relevant actions to tackle and minimize future occurrences.

- Repetitive patterns of medication errors should ideally be isolated and scrutinized.

- An unresolved inherent weakness in a healthcare system is otherwise just a matter of another explosion in the future if we give up on change.

In a root cause analysis (RCA), causal statements [something (cause) leads to something (effect) which increases the likelihood that the adverse event (event) will occur] must follow 5 rules.

- Clearly show the "cause" and "effect" relationship.

- Negative descriptors may not be used in causal statements.

- Each human error should have a preceding cause.

- Each "at-risk" behaviour or violation or procedural deviation, should have a preceding cause.

- Failure to act is only causal when there was a pre-existing duty to act.

Examples:

- Old wiring in the ICU was not replaced leads to frequent short circuit (wire trip), which results in electrical fire in the ICU.

- Doctors are scheduled 80 hours per week, which led to increased levels of fatigue, increasing the likelihood that dosing instruction would be misread.

Monitoring for Medication Errors

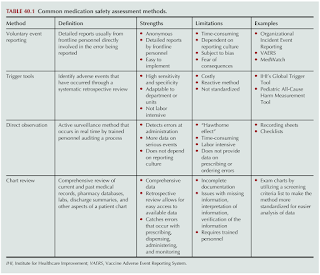

Several approaches have been taken to assess medication safety in acute care, community and ambulatory care settings.

- Unfortunately, many errors are not discovered when some institutions rely solely on voluntary reporting by their employees.

Medication Error Reporting System (MERS) is a national reporting system introduced by the Pharmaceutical Services Programme, Ministry of Health Malaysia since 2009.

- All healthcare professionals from both public and private sectors are encouraged to report detected medication errors.

- Reports can be submitted through either online channel or manual Medication Error Reporting Form.

Part of a strategic medication safety plan needs to include working to create and sustain a just culture.

- Just culture is about establishing a balance between the accountability of the organization to design safe systems and the accountability of the employee to make safe behavioural choices.

- This is in contrast to a "blame culture" where individual persons are fired, fined or otherwise punished for making mistakes, but where the root causes leading to the error are not investigated and corrected.

Medication System Improvement

The 5R's of medication administration (The right patient is given the right medication, at the right dose, at the right time, and via the right route) is merely broadly stated goals or desired outcomes of safe medication practices that offer no procedural guidance on how to achieve these goals.

- Hence, many errors, including lethal errors, have occurred in situations where practitioners believed they had verified the five rights.

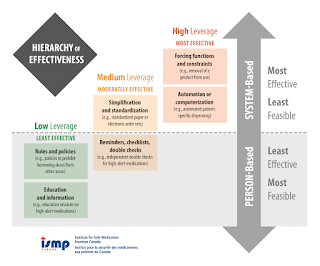

- In fact, one that relies solely on the performance of an inherently fallible human being is a low-leverage strategy in ISMP's Hierarchy of Effectiveness of Risk Reduction Strategies.

Medication Risk Reduction Strategies

- Minimise the availability of multiple medicines strengths kept in facility.

- Use Tall Man lettering

- Use additional warning labels for LASA medicines.

- Store LASA medications (Look Alike, Sound Alike) separately from their LASA pairs.

- Sharing on near misses or actual medication errors among colleagues.

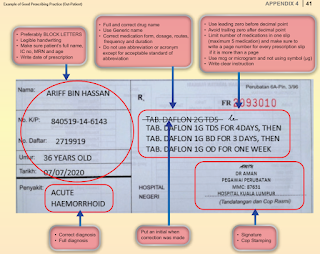

Good Prescribing Practice

- Prescription should be written in a clear legible manner.

- Use only standard abbreviations approved by the facility.

- Do not use unnecessary decimal points or terminal zeros after a decimal point.

- Place a zero in front of a leading decimal point.

Good Dispensing Practice

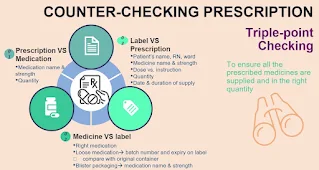

- Identify you patient by 2 identifiers, whereby patient's full name is compulsory.

- Triple-point independent counter-checking should be conducted by a second person, other than the staff who did the previous filling and labelling tasks.

High Alert Medications (HAMs)

High alert medications (HAMs) are defined as medications that bear a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when these medications are used in error.

- The associated medication mishaps may or may not be more common than other medications.

Categories of high alert medications include

- Adrenergic agonists, IV (e.g. adrenaline, phenylephrine, noradrenaline)

- Adrenergic antagonists, IV (e.g. propranolol, labetalol)

- Anaesthetic agents, general, inhaled and IV (e.g. propofol, ketamine)

- Antiarrhythmics, IV (e.g. lignocaine, amiodarone)

- Antithrombotic agents (e.g. warfarin, heparin, enoxaparin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, fondaparinux, tirofiban, tenecteplase)

- Antivenom (e.g. sea snake, cobra, pit viper antivenom)

- Chemotherapeutic agents, parenteral and oral

- Epidural and intrathecal medications

- Glyceryl trinitrate injection

- Immunosuppressant agents (e.g. azathioprine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus)

- Inotropic medications, IV (e.g. digoxin, dobutamine, dopamine)

- Insulin, subcutaneous and IV

- Magnesium sulphate injection

- Moderate and minimal sedation agents, oral, for children (e.g. chloral hydrate, midazolam, ketamine [using the parenteral form])

- Moderate sedation agents, IV (e.g. dexmedetomidine, midazolam, lorazepam)

- Neuromuscular blocking agents (e.g. pancuronium, atracurium, rocuronium, vecuronium)

- Opioids, including IV, oral and transdermal

- Oxytocin, IV

- Parenteral nutrition preparations

- Potassium salt injections

- Sodium chloride for injection, hypertonic (greater than 0.5% concentration)

- Dextrose, hypertonic (20% or greater)

Sound Alike Medications

Drugs with similar names are a threat to patient safety, and pharmacists must be on high alert when filling and dispensing these medications.

Few examples include:

- Amlodipine and Felodipine

- Carbimazole and Carbamazepine

- Carboplatin and Cisplatin

- Chlorpromazine and Carbamazepine

- Clomipramine and Clomiphene

- Cotrimoxazole and Clotrimazole

- Cysloserine and Cyclosporine

- Dimenhydrinate and Diphenhydramine

- Dopamine and Dobutamine

- Eribulin and Epirubicin

- Metformin and Methotrexate

- Neurobion and Neurontin

- Nicardipine and Nifedipine

- Oxycodone and Oxycontin

- Progyluton and Progynova

- Risperidone and Ropinirole

- Saxagliptin and Sitagliptin

- Sulfadiazine and Sulfasalazine

- Vinblastine and Vincristine

Summary

Medication safety is a journey with no end, because we can never perfect humans or equipment, but we can create more reliable systems.

- The responsibility for accurate medication administration does not lie with a single individual, but lies with multiple individuals, including organizational leaders.

External Links

- Medication Error (ME) Reporting

- 2025 Medication Error Reporting System

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, 2000

- Guidelines on Implementation Incident Reporting and Learning System 2.0, 2017

- Malaysia Patient Safety Goals 2.0, 2021

- The ten 'R's of safe multidisciplinary drug administration, 2015

- Guide on Handling Look Alike, Sound Alike Medications, 2012

- ISMP's List of Error-Prone Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations, 2024

- Guideline on Safe Use of High Alert Medications (HAMs), 2020

- ISMP List of High-Alert Medications in Acute Care Settings, 2018

- Preventing Prescription Error Quick Guide, 2020

- Australia - APINCHS classification of high risk medicines

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment