Epilepsy

Introduction

Epilepsy is a disorder characterised by a tendency to experience recurrent seizures. The International League Against Epilepsy's definition is 'a disease of the brain defined by:

- at least 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart

- 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years

- diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome.'

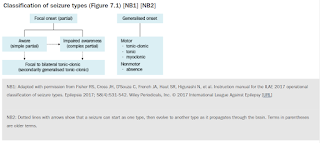

All seizures can be described based on the patient's symptoms.

- Motor symptoms include sustained rhythmical jerking movements (clonic), limp or weak muscles (atonic), muscle twitching (myoclonus) and rigid or tense muscles tonic).

- Non-motor symptoms include changes in sensation, emotions, thinking or cognition. Absence seizures typically present as staring spells.

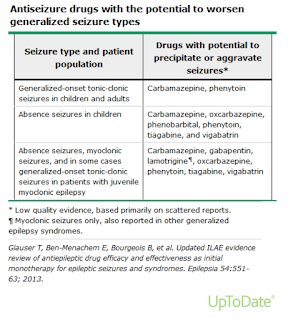

- Seizure type has important implications in the choice of antiseizure medications.

- Epilepsy can be the primary problem or a symptom of another brain disorder (e.g. brain tumour, injury, stroke). About half the patients who have a seizure for the first time do not have another, and do not have epilepsy.

- The link between epilepsy and mental illness is bidirectional as people with epilepsy have an elevated prevalence of several psychiatric disorders (including depression, anxiety and psychosis) and patients with depression, anxiety and psychosis have an increased risk of developing new-onset epilepsy. Ideally, optimise the treatment of epilepsy before prescribing psychotropics.

When to Start Treatment

Immediate antiseizure medication therapy is usually not necessary in individuals after a single seizure, particularly if a first seizure is provoked by factors that resolve.

- Antiseizure medication treatment is generally started after two or more unprovoked seizures, because the recurrence proves that the patient has a substantially increased risk for repeated seizures, well above 50 percent.

Seizures are more likely to recur in patients with focal (partial) seizures, epileptiform abnormalities on EEG, abnormal neurological examination or a lesion on neuroimaging.

- In these situations, consider starting treatment after the first seizure.

Choosing an Antiseizure Medication

The selection of a specific antiseizure medication for treating seizures must be individualized considering

- Drug effectiveness for the seizure type or types

- Potential adverse effects of the drug

- Interactions with other medications

- Comorbid medical conditions, especially, but no limited to, hepatic and renal disease

- Age and gender, including childbearing plans

- Lifestyle and patient preferences

- Cost

DynaMed's recommendation

- Valproate (and sodium valproate and valproic acid) should be avoided if possible in women and girls of childbearing potential.

- For focal epilepsy

- First-line therapy is lamotrigine; if poorly tolerated, consider carbamazepine or levetiracetam as reasonable alternatives.

- For drug-resistant focal epilepsy, consider adjunct antiseizure medications with any of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lacosamide, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, pregabalin, topiramate, valproate, and zonisamide.

- For genetic generalized epilepsy or unclassified epilepsy

- First-line therapy is valproate.

- If valproate is poorly tolerated or may not be appropriate (such as in persons who may become pregnant)

- give lamotrigine or topiramate.

- consider levetiracetam or lamotrigine in persons who may become pregnant.

- For drug-resistant generalized epilepsy, consider adjunct antiseizure medications with any of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, ethosuximide, valproate, and topiramate.

Titrating Antiseizure Medication

Most antiepileptic drugs are started at a low dose, which is slowly increased to the initial target.

- This is especially important for lamotrigine, to reduce the risk of serious adverse skin reactions.

- An exception is phenytoin, which can be started at the initial target dose or even with a loading dose.

If seizures are not controlled by the first antiepileptic drug, a second drug with different mechanisms of action is added. The dose of the second drug is adjusted as for the first.

- If combined therapy is effective, the first drug may be gradually withdrawn to find out if monotherapy with the second drug is effective. However, many patients prefer to continue combination therapy rather than risk the seizures returning.

- If ≥ 2 monotherapy regimens fail to control seizure, consider combination antiepileptic therapy (combination of 2 or at most 3).

Discontinuing Antiseizure Medication

Consider discontinuing antiepileptic drugs in patients who are seizure-free for at least 2 years.

- Discuss with patient the risks and benefits of continuing or discontinuing antiepileptic drug therapy, including driving, employment, fear and risks of further seizures, and concerns about long-term antiepileptic therapy.

- For patients who will discontinue antiepileptic therapy, discontinuation should occur over the course of a few months (longer for barbiturates and benzodiazepines) and involve withdrawal of 1 drug at a time.

When therapy is withdrawn after at least 2 seizure-free years, the risk of seizures recurring is about 50%. Factors that predict a high risk include:

- symptomatic (structural, metabolic, immune, infectious) epilepsy

- neurological abnormalities on examination

- a history of seizures that are difficult to control

- epileptiform abnormalities on EEG

- abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography

- recurrence after past attempts to withdraw all antiepileptic therapy.

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy has such a high recurrence rate that it is best not to withdraw therapy, at least not until many years without seizures of any type (including jerks).

Generic Substitution

The use of generic versus brand-name antiseizure medications in people with epilepsy has attracted much attention and debate, and the evidence is mixed in terms of whether generic substitution of antiseizure medications has an adverse impact on seizure control and toxicity.

- Using pharmacokinetic data submitted to the FDA, one study found that while most generic antiseizure medications provide total drug delivery similar to the reference product, differences in peak concentrations were more common, and switches between generic products caused greater changes in plasma drug concentrations than generic substitution of the reference product. It is possible that the small, FDA-allowed variations in pharmacokinetics between a name brand and its generic equivalent (and between generic equivalents) can lead to either toxicity or seizures in some patients who, for unknown reasons, are particularly vulnerable.

- By contrast, a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven trials in which the frequency of seizures was compared between a brand-name antiseizure medication and a generic alternative found no difference in the odds of seizures between treatment regimens.

In 2017, the CHM has reviewed spontaneous adverse reactions received by the MHRA and publications that reported potential harm arising from switching of antiepileptic drugs in patients previously stabilised on a branded product to a generic. The CHM concluded that reports of loss of seizure control and/or worsening of side-effects around the time of switching between products could be explained as chance associations, but that a causal role of switching could not be ruled out in all cases. The following guidance has been issued to help minimise risk:

- Different antiepileptic drugs vary considerably in their characteristics, which influences the risk of whether switching between different manufacturers’ products of a particular drug may cause adverse effects or loss of seizure control;

- Antiepileptic drugs have been divided into 3 risk-based categories to help healthcare professionals decide whether it is necessary to maintain continuity of supply of a specific manufacturer’s product. These categories are listed below;

- Category 1

- Carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone.

- For these drugs, doctors are advised to ensure that their patient is maintained on a specific manufacturer’s product.

- Category 2

- Clobazam, clonazepam, eslicarbazepine acetate, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, rufinamide, topiramate, valproate, zonisamide.

- For these drugs, the need for continued supply of a particular manufacturer’s product should be based on clinical judgement and consultation with the patient and/or carer taking into account factors such as seizure frequency, treatment history, and potential implications to the patient of having a breakthrough seizure. Non-clinical factors as for Category 3 drugs should also be considered.

- Category 3

- Brivaracetam, ethosuximide, gabapentin, lacosamide, levetiracetam, pregabalin, tiagabine, vigabatrin.

- For these drugs, it is usually unnecessary to ensure that patients are maintained on a specific manufacturer’s product as therapeutic equivalence can be assumed, however, other factors are important when considering whether switching is appropriate. Differences between alternative products (e.g. product name, packaging, appearance, and taste) may be perceived negatively by patients and/or carers, and may lead to dissatisfaction, anxiety, confusion, dosing errors, and reduced adherence. In addition, difficulties for patients with co-morbid autism, mental health problems, or learning disability should also be considered.

- If it is felt desirable for a patient to be maintained on a specific manufacturer’s product this should be prescribed either by specifying a brand name, or by using the generic drug name and name of the manufacturer (otherwise known as the Marketing Authorisation Holder);

- This advice relates only to antiepileptic drug use for treatment of epilepsy; it does not apply to their use in other indications (e.g. mood stabilisation, neuropathic pain);

Lifestyle Modifications

Avoid precipitating factors of seizures, such as sleep deprivation and alcohol.

Diet

- A ketogenic diet is a high fat, low carbohydrate, adequate protein diet which is associated with seizure reduction in adults with generalized and partial epilepsy refractory to treatment.

- Low glycaemic index and modified Atkins diets have also found beneficial in adults with epilepsy.

Driving and Epilepsy In Malaysia

In Malaysia, the Akta Pengangkutan Jalan (APJ) 1987 and Kaedah-Kaedah Kenderaan Motor (Lesen Memandu) 1992 applies, and states:

- Under Section 30 (2) and (3) APJ 1987, the Pengarah of JPJ may refuse an application for a licence if the licensee is found to have a condition (disease or disability) that may endanger other road users. In this context, Kaedah 18 dan Kaedah-Kaedah Kenderaan Motor (lesen memandu) 1992 clearly states 'epilepsy' as one such condition; this applies to all and any forms of licences.

- If a licensee has obtained a licence before developing this condition, the Pengarah can revoke this licence under Section 30 APJ 1987 based on a medical report from any medical officer stating the level of disease/disability.

Legally, the doctor is not duty bound to notify JPJ. Generally, the decision to drive or not to drive is a choice best made after discussions between the treating physician and patient. Some conditions that may allow for safe driving include:

- Well-controlled epilepsy, and the patient is on treatment.

- Seizure freedom for at least 1 year, off or on treatment.

- Preceding aura - however, auras may not occur with every seizure, or the driver may not have enough space on the road to pull over despite an aura signalling an impending seizure.

- Purely nocturnal seizures.

Someone who is a newly diagnosed epileptic and is being started on medication is advised to stop driving for 6-12 months, until the seizures have stabilised and any drug-related side effects have settled.

Certain occupations are prohibited for people with epilepsy - these include driving heavy machinery e.g. tractors and public buses, as well as flying commercial or military airplanes. As such, obtaining driving licences in these situations is clearly not possible.

Driving is considered a privilege, not a right. If a patient’s epilepsy is against him/her obtaining a driver’s licence, use of public transport or carpooling is encouraged.

Summary

External Links

- DynaMed - Epilepsy in Adults

- Seizure outcomes following the use of generic versus brand-name antiepileptic drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2010

- Assessing bioequivalence of generic antiepilepsy drugs, 2011

- Antiepileptic drugs: updated advice on switching between different manufacturers’ products, 2017

- Malaysia Consensus Guideline on the Management of Epilepsy, 2017

- Instruction manual for the ILAE 2017 operational classification of seizure types, 2017

- Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy, 2020

- Bioequivalence and switchability of generic antiseizure medications (ASMs): A re-appraisal based on analysis of generic ASM products approved in Europe, 2021

Comments

Post a Comment