Low Back Pain

Introduction

Low back pain affects 60-80% of people at some stage in their lives (most common between the ages of 35 and 55 years) and is often recurrent.

- Acute back pain is generally regarded as lasting less than 6 weeks, subacute for 6-12 weeks and chronic longer than 12 weeks.

Clinical Features

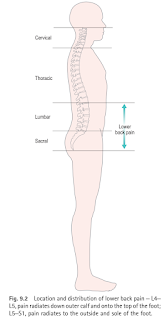

Pain in the lower lumbar or sacral area is usually described as aching or stiffness.

- Depending on the cause, pain might be localized or more diffuse.

- In case of acute injury, the symptoms come on quickly, and there will be a reduction in mobility.

Risk Factors

- Heavy physical work

- Frequent bending, twisting or lifting

- Prolonged static postures

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Physical inactivity

NOTE: Low back pain can be caused by gastrointestinal problems (e.g. peptic ulcer or pancreatitis) or genitourinary conditions (e.g. kidney stones, pyelonephritis) but low back pain is not the major presenting symptom.

Management

Most patients (95%) who present in the pharmacy will have simple back pain that will, in time, resolve with conservative treatment.

- The remaining cases will have back pain with associated nerve root compression.

- Serious underlying pathology is very rare, with infection and malignancy accounting for less than 1% of cases.

Symptoms for referral

- Numbness

- Fever

- Persistent and progressively worsening pain

- Failure of symptoms to improve after 4 week

Conservative Treatment

Bed rest was once widely prescribed for patients with low back pain.

On the other hands, exercise programmes can help with acute back pain and have been shown to reduce recurrence.- Advise patients with acute or subacute low back pain to remain active as tolerated.

Oral Analgesics

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for 7 to 10 days is widely advocated.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain, 2008

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain, 2016

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute low back pain, 2020

It has long been claimed that caffeine enhances analgesic efficacy.

- A Cochrane review showed that there was a small but statistically significant benefit with caffeine used at doses of 100 mg or more, which was not dependent on the pain condition or type of analgesic.

Skeletal Muscle Relaxants

Skeletal muscle relaxants may improve short-term pain compared to placebo; however, addition of skeletal muscle relaxants to NSAIDs does not appear to improve pain or functional status compared to NSAIDs alone.

Examples: Baclofen, eperisone, orphenadrine and tizanidine.

Topical Preparations

A 2015 systematic review found that topical NSAIDs were significantly better than placebo in 50% pain relief.

- Topical NSAIDs have fewer side effects than systemic therapy, with the most commonly reported adverse events being skin reactions at the site of application.

Rubefacients (also known as counterirritants, e.g. salicylates, nicotinates, menthol, camphor, capsaicin, turpentine oil) have been incorporated into topical formulations for decades.

- They cause vasodilation, producing a sensation of warmth that distracts the pain from experiencing pain.

- However, the larger, more recent studies have shown no effect for salicylate-containing rubefacients.

- A review by Mason et al. concluded that capsaicin appears to have only poor to moderate efficacy in chronic musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain.

Complementary Therapies

Considering growing public interest and the expanding volume of literature, Cochrane reviews have been conducted on

- Heat and cold therapy

- These range from hot water bottles, heat pads and infrared lamps to ice packs.

- Many of the studies were of poor methodological quality, but evidence exists that continuous heat wrap therapy reduces pain and disability in the short term to a small extent.

- Herbal remedies

- The Cochrane review reported on 5 active constituents - Capsicum frutescens (Cayenne), Harpagophytum procumbens (devil's claw), Salix alba (white willow bark), Symphytum officinale (comfrey root extract) and Solidago chilensis (Brazilian arnica).

- The authors concluded that the best evidence was for the use of cayenne.

- Acupuncture

- The available evidence for acupuncture in acute low back pain does not support its use, although, if used in chronic back pain, acupuncture is more effective for pain relief than no treatment in the short term.

- Massage

- Findings appear to show benefit compared to placebo in the short-term but not long-term. However, all 25 randomized control trials identified for the review were of low quality.

External Links

- Systematic review of topical capsaicin for the treatment of chronic pain, 2004

- Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain: an updated systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration, 2005

- Superficial heat or cold for low back pain, 2006

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain, 2008

- Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low-back pain and sciatica, 2010

- Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults, 2014

- Salicylate-containing rubefacients for acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults, 2014

- Herbal medicine for low‐back pain, 2014

- Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults, 2015

- Massage for low‐back pain, 2015

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain, 2016

- Paracetamol for low back pain, 2016

- Topical analgesics for acute and chronic pain in adults - an overview of Cochrane Reviews, 2017

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute low back pain, 2020

- Efficacy, acceptability, and safety of muscle relaxants for adults with non-specific low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis, 2021

- Comparative effectiveness and safety of analgesic medicines for adults with acute non-specific low back pain: systematic review and network meta-analysis, 2023

Comments

Post a Comment