Atrial Fibrillation

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is a common supraventricular tachyarrhythmia caused by uncoordinated atrial activation and associated with an irregular ventricular response.

Atrial fibrillation is classified according to clinical pattern, with patients sometimes progressing from one pattern to another.

- These categories reflect observed episodes of AF and do not suggest the underlying pathophysiological process.

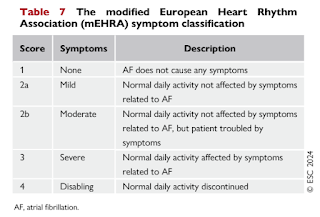

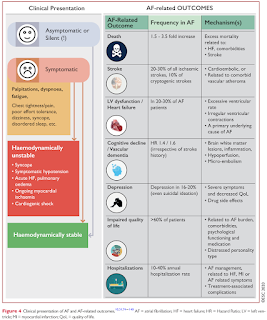

Symptoms

Patients with AF may have various symptoms but 50-87% are initially asymptomatic, with possibly a less favourable prognosis.

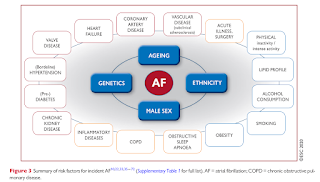

Risk Factors

The AF-CARE Approach

The AF-CARE approach builds upon the AF Better Care pathway in 2020 and notably, takes account of the growing evidence base that therapies for AF are most effective when associated health conditions are addressed.

- C - Comorbidity and risk factor management

- A - Avoidance of stroke and thromboembolism in patients with risk factors, focused on appropriate use of anticoagulant

- R - Reduce symptoms by rate and rhythm control to reduce hospitalization or improve prognosis

- E - Evaluation and dynamic reassessment

NOTE: AF Better Care pathway in 2020

- A - Anticoagulation/Avoid Stroke

- B - Better symptom control

- Rate control

- Rhythm control

- C - Cardiovascular and comorbidity optimization

Comorbidity and Risk Factor Management

A broad array of comorbidities are associated with the recurrence and progression of AF.

Avoid Stroke and Thromboembolism

Thromboembolism is a major complication of AF which may result in stroke or death.

- The default approach should therefore to provide oral anticoagulant to all eligible patients, except those at low risk of incident stroke or thromboembolism.

CHA2DS2-VA (excluding gender) score may be used to assist in decisions on oral anticoagulant therapy.

- The inclusion of gender in CHA2DS2-VASc complicates clinical practice because female is an age-dependent stroke risk modifier rather than a risk factor per se.

- Oral anticoagulant are recommended in those with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 2 or more and should be considered in those with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 1.

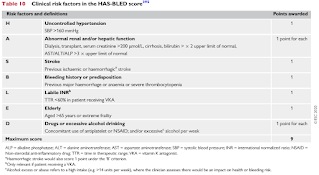

When initiating antithrombic therapy, modifiable bleeding risk factors should be managed to improve safety.

- Strict control of hypertension

- Advice to reduce excess alcohol intake

- Avoidance of unnecessary antiplatelet or anti-inflammatory agents

- Attention to OAC therapy (adherence, review of interacting medications)

Clinicians should consider the balance between stroke and bleeding risk - as factors for both are dynamic and overlapping, they should be re-assessed at each review depending on the individual patient.

- Patients with non-modifiable risk factors should be reviewed more often.

Several risk scores for bleeding, such as the HAS-BLED score, have been developed to account for a wide range of clinical factors.

- Systematic reviews and validation studies in external cohorts have shown contrasting results and only modest predictive ability.

- ESC task force does not recommend a specific bleeding risk score given the uncertainty in accuracy and potential adverse implications of not providing appropriate oral anticoagulant to those at thromboembolic risk.

The few absolute contraindications to oral anticoagulants include active serious bleeding, associated comorbidities (severe thrombocytopenia, severe anaemia under investigation, etc), or a recent high-risk bleeding event such as intracranial haemorrhage.

NOTE: Antiplatelet therapy is not recommended as an alternative to anticoagulation in patients with AF to prevent ischemic stroke and thromboembolism.

Reduce Symptoms by Rate and Rhythm Control

Most patients diagnosed with AF will need therapies and/or interventions to control heart rate, revert to sinus rhythm, or maintain sinus rhythm to limit symptoms or improve outcomes.

Limiting tachycardia is an integral part of AF management and is often sufficient to improve AF-related symptoms.

- Rate control is indicated as initial therapy in the acute setting, in combination with rhythm control therapies, or as the sole treatment strategy to control heart rate and reduce symptoms.

- Lenient rate control with a resting heart rate of < 110 b.p.m. should be considered as the initial target for patients with AF, with stricter control reserved for those with continuing AF-related symptoms (e.g. tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy).

Pharmacological rate control can be achieved with

- Beta-blockers

- Often first line

- Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (e.g. diltiazem and verapamil)

- First line treatment in severe asthma or COPD

- Not suitable in AF patients with LVEF <40%

- Digoxin

- Some antiarrhythmic drugs also have rate-limiting properties (e.g. amiodarone, dronedarone, sotalol) but generally they should be used only for rhythm control.

- Due to its broad extracardiac adverse effect profile, amiodarone is reserved as a last option when heart rate cannot be controlled even with maximal tolerated combination therapy, or in patients who do not qualify for atrioventricular node ablation and pacing. Many of the adverse effects from amiodarone have a direct relationship with cumulative dose, restricting the long-term value of amiodarone for rate control.

Rhythm control refers to therapies dedicated to restoring and maintaining sinus rhythm. These treatments include

- Electrical cardioversion

- Anti-arrhythmic Drugs (AADs)

- Examples: Flecainide, propafenone, amiodarone, ibutilide, vernakalant

- All AADs may produce serious cardiac (proarrhythmia, negative inotropism, hypotension) and extracardiac adverse effects (organ toxicity, predominantly amiodarone). Drug safety, rather than efficacy, should determine the choice of drug.

- Percutaneous catheter ablation, endoscopic and hybrid ablation and open surgical approaches

External Links

- ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Atrial Fibrillation, 2020

- ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation, 2024

- Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation, 2010

- A Novel User-Friendly Score (HAS-BLED) To Assess 1-Year Risk of Major Bleeding in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey, 2010

Comments

Post a Comment